Reaching the Middle Ground for Addressing Patients’ Beliefs in Sorcery: Experiences of Papua New Guinean Nurses

Dr Gabriel Kuman is a researcher and senior lecturer at the Social and Religious Studies Department of the Divine Word University in Madang, Papua New Guinea.

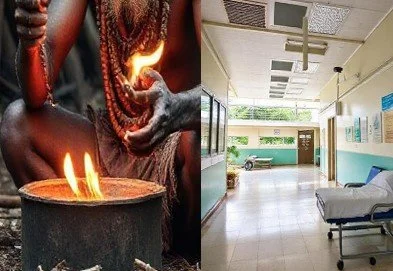

Here he explores the interplay between beliefs and science in relation to nurses and patients and what happens when beliefs around sorcery cross into the medical world of hospitals.

by Gabriel Kuman

14 November 2025

Sicknesses and deaths are an uncompromising experience for people in many cultures of the Global South. People understand that sickness often leads to death – that is the fact of life; it is inevitable. However, it is frequently challenging and perhaps complex for people to accept it too lightly. The fear of losing a loved one during critical times of sickness often puts people in desperate situations to take desperate actions, with the ultimate goal of restoring and achieving good health.

Advancing beyond the twenty-first century, with technological developments overtaking us by storm globally, people in the Global South, especially Papua New Guineans, could not shake off their ancient beliefs in sorcery and witchcraft. Coming from a traditionalist, integrated, and animistic cultural background, every illness and death is attributed to supernatural causes – be it the nature spirits, spirits of the dead relatives, or other living human beings through sorcery and witchcraft.

Even if an illness or a death is linked to a medical cause, people would still find someone to blame.

During my doctoral fieldwork, nurses reported that they often came across patients who believed that evil forces like sorcery and spirits or relationship issues caused their illnesses. Occasionally, the relatives of certain patients called the Glasman[1] to the hospital premises to perform healing rituals. When disease persisted, some patients felt the need to return home to ‘straighten things out’ due to broken relationships or to seek the assistance of a glasman to find out the causes.

Alice Street, a social anthropologist who conducted a hospital ethnography in Madang Province, reports that many patients organized “…village meetings to find out the bad intentions of relatives, providing compensation in the form of pig meat to people they had aggrieved, and consulting medical diviners” (2010, 266).

Oftentimes, the nurses had no answers when dealing with people’s beliefs in sorcery and glasman. What are the nurses’ reactions? How do they respond to these issues? The opinions on disease causality related to sorcery and witchcraft are divided and varied among nurses. While some nurses believed in the existence of malevolent sorcery and witchcraft and their effects, others viewed them as superstitious, hence counterproductive to established scientific facts, explanations, diagnoses, and treatments. They dismissed people’s beliefs in supernatural causes and sought to provide biological or physiological causes. A female nurse said:

“We give them the medical point of view. We never talked much about the cultural beliefs.”

In a follow-up question, I asked whether the people understood and accepted the scientific explanations of the disease causation. Most nurses admitted that people’s beliefs are still strong. Another female nurse stated:

“We tried to provide medical explanations and help them understand the situations. But they stood firm in their beliefs.”

In describing such beliefs and practices against the Western dualistic worldview, Paul Hiebert, a missionary anthropologist who worked in India for many years, develops a middle zone called the “Excluded Middle” (Hiebert 1982, 43–5), where the beliefs in spirits, demons, sorcery, witchcraft, and the invisible powers of this world are often excluded or dismissed as superficial and nonexistent. Despite this widespread rejection, these beliefs and practices continue to re-emerge and persist forcefully in cultures of the developing world, especially in the Global South. My research shows that despite the availability of advanced conventional medicine, people still seek multiple avenues in non-conventional medicine, such as diviners, glasman, traditional herbalists, and prayer warriors for their medical needs.

Based on his experience as a missionary in India, Hiebert argues that we cannot simply dismiss them. We have to provide an answer for them.

In my study, some nurses reported that they “tried their very best to explain” scientifically, as they had been trained to explain disease causation in naturalistic terms.

Did they convince the people to believe in scientific explanations? Not really!

According to the nurses’ reports, the people are still adamant in their beliefs. Others noted that they could not do much to stop the glasman but felt obliged to allow them to perform healing rituals secretly inside hospital premises. “We advise them (glasman) to do it secretly so that it is not seen by other patients and guardians at the hospital,” a female nurse said.

Some nurses described them as highly superficial and repugnant to established scientific facts and their Christian belief in God. Hence, they ordered the glasman to leave the hospital premises and shun their practices. As one male nurse reported, he warned the glasman and his team of the confusion they had caused and ordered them to leave the hospital premises immediately.

Other nurses instructed the patients to go home and practice their beliefs and later return for medication if the disease persists. While this is true, a few nurses from Kudjip Nazarene General Hospital in Jiwaka Province, said that instead of dismissing the people’s beliefs in sorcery and glasman, they replaced them with the belief in the Christian God and reinforced this with counselling and prayer for God’s protection and healing. A female nurse reported:

“I advised them, ‘Do not believe in Satan. You must believe in God because God is more powerful than Satan and his Evil forces.’”

The nurses reported that the approach was effective, as it enabled patients to leave behind their belief in sorcery and turn to God in prayer, which further contributed to their healing process. Further reinforcement through post-hospital follow-ups by the hospital chaplains ensures that patients are reoriented into their families and communities. The chaplains’ involvement in the communities minimizes potential escalation of violence related to sorcery.

While supporting this approach, Paul Hiebert agrees that we should leave aside the Platonic dualism and develop a holistic theology that includes the “body and soul” (1982, 45–6) in our discussions and interventions. The nurses and chaplains at Kudjip Nazarene General Hospital complemented their medical knowledge and skills with the cultural beliefs in sorcery that reached the middle ground, or what Hiebert calls the “Excluded Middle” (1982, 43-5). This helps them provide holistic and meaningful care to the patients, families, and the entire community.

However, Hiebert warns us further that such an approach might make Christianity become like a magic institution where people would come to take part in Christian rituals and turn prayers into “formula or chant to force God to do one’s will by saying or doing the right thing” (1982, 46). While the approach taken by the nurses and chaplains is good, they must, as much as possible, avoid giving false hopes and expectations that healing is inevitable and imminent by turning to God in prayer.

To do this positively, Hiebert provides an example in his concluding remarks that

“…true answers to prayer are those that bring the greatest glory to God, not those that satisfy my immediate desires (1982, 47). ”

I concur with Hiebert and recommend that accurate answers to prayers should be sincere, forthright, and honest to the fact that sickness, healing, and death are the natural processes of life, and for humans, particularly Christians, there is always hope of final resurrection and reunion in Heaven.

Endnotes

[1] Glasman, or sometimes glasmeri, are PNG Tok Pisin (lingua franca of PNG) expressions that refer to a man or a woman who proclaims to possess special magical powers to see the disease causality through the eyes of an invisible glass. Oftentimes, the glasman or glasmeri would connect disease causality with a living human being, often a close relative of the sick or deceased person, which will eventually lead to a sorcery accusation and killing. This is the negative aspect of the work of glasman or glasmeri.

References

Hiebert, P. G. 1982. “The Flaw of the Excluded Middle.” Missiology: An International Review 10 (1): 35–47.

Kuman, G. 2025. “Towards a Holistic Gutpela Sindaun Model of Care in Nursing for Papua New Guinea.” Doctoral Dissertation, ProQuest, Pasadena: Fuller Theological Seminary.

Street, A. 2010. “Belief as Relational Action: Christianity and Cultural Change in Papua New Guinea.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 16 (2): 260–78.